- Home

- Ferida Wolff

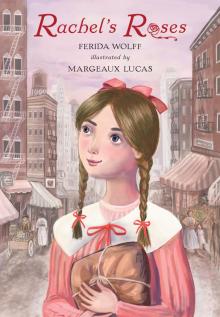

Rachel's Roses

Rachel's Roses Read online

Copyright © 2019 by Ferida Wolff

Illustrations © 2019 by Margeaux Lucas

All Rights Reserved

HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

www.holidayhouse.com

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wolff, Ferida, 1946– author. | Lucas, Margeaux, illustrator.

Title: Rachel’s roses / Ferida Wolff; illustrated by Margeaux Lucas.

Description: New York : Holiday House, 2019. | Summary: In the Lower East Side of Manhattan during the early 1900s, third-grader Rachel’s mother boldly starts her own dressmaking business and Rachel discovers the perfect way to set herself apart from tagalong little sister Hannah on Rosh Hashanah.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018060600 | ISBN 9780823443659 (hardback)

Subjects: | CYAC: Dressmakers—Fiction. | Sisters—Fiction. | Rosh ha-Shanah—Fiction. | Jews—United States—Fiction. | Lower East Side (New York, N.Y.)—History—20th century—Fiction. | New York (N.Y.)—History—1898–1951—Fiction. | BISAC: JUVENILE FICTION / Historical / United States / 20th Century. | JUVENILE FICTION / Religious / Jewish. | JUVENILE FICTION / Social Issues / Prejudice & Racism.

Classification: LCC PZ7.W82124 Rac 2019 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018060600

ISBN: 9780823443659 (hardcover)

Ebook ISBN 9780823443932

v5.4

a

With love for my mother,

Shirley Mevorach,

who helped me remember

and whom I now remember

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. Hot Pepper

2. Mama’s Dream

3. Being Fancy

4. Button Shopping

5. Feeling Mean

6. Getting a Job

7. Working Hard

8. Secrets

9. Lost Button

10. Lost Hannah

11. Rachel’s Roses

Author’s Note

• one •

HOT PEPPER

Rachel ran up the stoop to her apartment above Skolnik’s Candy Store in the tenement building. She had been waiting all day for school to be over. She and her friends were going to have a jump rope contest, and she hoped she wouldn’t have to include Hannah. Her little sister was always ruining their games.

“Hello, Bubbie,” she called to her grandmother.

Bubbie was hanging a load of dripping wash on the clothesline outside the kitchen window.

“Mama said you shouldn’t be standing so much because of your sore feet.”

“Ah, Racheleh, Mr. Kupferman doesn’t pay me to give him back wet laundry. Besides, if you twist your arm, you don’t feel your toothache.”

Bubbie was always saying things like that. Most of the time Rachel didn’t understand what she meant. When Rachel asked her to explain, Bubbie just smiled and said, “Someday you’ll know.”

Rachel kissed her grandmother on the cheek, put down her schoolbooks, and grabbed the old clothesline her friends used as a jump rope.

Hannah peeked out from under the small kitchen table.

“Where are you going?” she asked.

“Downstairs. Sophie, Simcha, and Mollie are waiting for me. We’re having a hot pepper contest.”

“I can do hot pepper,” Hannah said.

“No you can’t,” said Rachel. “The rope goes too fast. You’ll fall and get hurt.”

“I run fast. Bubbie said so.”

“Running isn’t the same as jumping.”

“Then I’ll be an ender and turn the rope.”

“Take your sister, Racheleh,” Bubbie said. “She’s been in all day and needs some air. And see that she doesn’t get lost.”

Rachel didn’t see how Hannah could get lost. Her sister stuck to her closer than an eraser on a pencil.

“Come on then,” Rachel said.

“Wait. I have to get Bessie.”

Rachel dashed out the door. Hannah snatched up her rag doll, Bessie, and hurried behind. When Rachel’s friends saw Hannah, they groaned.

“Not again,” said Simcha.

“Why does she always have to play with us?” said Mollie, Simcha’s twin.

“Mama said I’m Rachel’s ’sponsibility,” said Hannah.

“Responsibility. And you don’t even know what that means,” said Rachel.

“I do too. It means you have to take care of me.”

Rachel pointed toward the metal steps.

“Sit down, Hannah. And don’t wander off.”

Rachel and Simcha found a space near Phil’s fruit pushcart and turned the rope while Sophie jumped.

“One-two-three-four-five-six-seven-eight,” they counted, making the rope go as fast as they could. Sophie missed. She became an ender and turned the rope with Rachel. Mollie got out after only two turns.

When it was Rachel’s turn, Hannah jumped in the middle of the turning rope with her and got all tangled up.

“Hannah!” scolded Rachel. “I told you to stay on the stoop. Hot pepper is too fast for you.”

“It was Bessie. She doesn’t know how to jump. I told her to stay on the steps but she wouldn’t listen.”

“Just like a sister I know,” said Rachel. She pointed to the stoop. Hannah sighed and went back to sit on the steps.

They straightened out the rope and the contest was on again. Rachel figured out that if she jumped with one foot at a time instead of both feet together, she would be less tired and could jump longer.

She was good at figuring things out. It was fun. She was the best in her class at arithmetic. She liked to understand how her world worked. She knew she could win the contest easily and be the best jumper on the block—if only Hannah wouldn’t get in the way.

Rachel was having a good jump when she saw her mother hurrying up the block with a large bundle in her arms.

Her mother never came home this early. What was wrong?

Rachel missed on purpose and ran to her mother just as Hannah scrambled off the stoop.

“How come you’re home now, Mama?” Rachel asked.

Mrs. Berger’s eyes glowed.

“A dream, Rachel,” she said. “Today I quit my job to begin a dream.”

“You quit, Mama?” said Rachel.

“Quit, fired, it’s all the same. What it means is that I can finally do what I’ve always wanted to do.”

Before Rachel could ask what that was, Mrs. Berger grabbed Hannah’s hand and the two of them scampered up the stoop and disappeared inside the house.

“Come on, Rachel,” called Simcha. “It’s my turn.”

Rachel just stood there, confused. Her mother had worked for Mr. Lempkin in the tailor shop. She sewed pretty lace collars onto dresses. She made nice, even buttonholes on suits. Mr. Lempkin said he made the finest suits in New York City and Mrs. Berger made the neatest buttonholes on Orchard Street.

Rachel’s mother had been lucky to have such a good job where she worked only from eight o’clock in the morning until seven o’clock at night. Many of the other mothers worked until nine or ten o’clock in the sweatshops. They spent the whole day leaning over their sewing machines until their backs hurt almost as much as Bubbie’s feet. Now maybe Mama would have to work in a sweatshop too.

“Rachel,” Simcha said again. “Come on.”

Rachel knew her family

needed her mother’s wages as much as the wages her father brought home from the shoe store. Even Bubbie took in laundry—and Rachel made the deliveries. How was it possible that Mama would quit?

This was one thing Rachel couldn’t figure out.

“I’ve got to go,” she told her friends.

As Rachel ran toward home, Sophie called out, “Rachel, you forgot your rope.”

Rachel kept running.

• two •

MAMA’S DREAM

“What did you mean about a dream, Mama?” Rachel asked as soon as she got in the door.

“Let me remove my hat, please,” Mrs. Berger said.

She sounded like the regular, practical mother she usually was, not the mother who would quit her job.

Bubbie had finished with the wash and was peeling potatoes into a bowl of water at the kitchen table.

“I jumped hot pepper, Bubbie,” said Hannah. “Just like Rachel.”

“You did not!” scolded Rachel. “You made me miss.”

“Next time I won’t.”

“There won’t be a next time. Bubbie, why does she have to do everything I do?”

“Reasons, you’re always looking for reasons. Because you’re the big sister. What better reason? Now let me get back to work. These potatoes won’t peel themselves.”

Mama put the fat paper bundle on the table next to the bowl. It looked like an overgrown potato Bubbie hadn’t peeled yet.

Sometimes Mr. Lempkin let Mama take home leftover scraps of material that were too small to make into anything. Mama was clever. With a little cutting here and a few stitches there, she would surprise them all. Bessie was made from one of Mama’s scrap bundles. But this was a very large bundle. It could make a hundred dolls.

Maybe it was the material for the new skirts Mama had promised to make them for Rosh Hashanah. Rachel usually had to wear something a neighbor or cousin had outgrown. While Mama would make it fit, it always felt wrong somehow.

Bubbie said that something new for the new year brought good luck. Rachel had a feeling they were going to need it.

Mrs. Berger untied the string and carefully unwrapped the package. Then she gently unfolded the material. It was all one piece, not the little snips of wool and cotton and lace Rachel had expected to see.

Rachel stared at the soft red plaid wool that covered the table. She couldn’t believe Mr. Lempkin would give away such fancy material.

“What’s this?” said Bubbie.

“This is Mrs. Golden’s Rosh Hashanah dress,” said Mama. “Or it will be soon. Mrs. Golden came into the store today to discuss the design for her dress with Mr. Lempkin. He showed her the pattern he had made and then she did the most extraordinary thing—she asked me what I thought of it! Can you imagine? I told her that the collar might be more fashionable if it came lower down the front and that the skirt would be more flattering if it wasn’t so full at the hips.

“Mr. Lempkin said, ‘Who’s the tailor here?’ But Mrs. Golden told him she liked my ideas better. Mr. Lempkin said if I wanted to design dresses, I would have to go somewhere else. I said, ‘I’ll do that, Mr. Lempkin.’ He gave me my day’s pay and the material Mrs. Golden had paid for and said goodbye. So now I’m Beryl Berger, dressmaker.”

Bubbie looked at Mama. She opened her mouth but then didn’t say anything. She turned back to the potatoes.

Splash. A potato plopped into the bowl. Rachel watched the water jump into the air. She figured out that four more potatoes would make the water overflow. It was easier thinking about potatoes than about what her mother was telling them.

“I’ll make such beautiful dresses that all of New York will want to wear a Beryl Berger creation.”

“Is that your dream, Mama?” Rachel said.

“Yes, Rachel. From the time I was a girl, younger than you, I wanted to make fancy dresses. Mrs. Golden’s will be my first.”

“I had a dream last night, Mama,” said Hannah. “It was about a big mouse that kept running away from me. I only wanted to play with it. I chased it but it got away.”

Mrs. Berger laughed.

“This is a different kind of dream, Hannah. It’s a dream that you have when you are awake.”

“Did you bring home material to make our skirts too?” asked Rachel.

“Oh,” said Mama. “In all the excitement I forgot about the skirts. Now that I’m out of work, there is no money to buy material. I’m afraid you and your sister will have to make do with your red wool skirts from last year.”

“But Mama, you promised!”

Mama wasn’t listening. She was describing to Bubbie the wonderful dress she would make for Mrs. Golden.

Rachel had already told her friends about her new skirt. Now she would show up at shul for prayers on the holiday like it was any old day of the year. Mama’s dream was starting to sound like a nightmare.

• three •

BEING FANCY

“Please, Mama,” said Rachel when her mother had finished talking. “Can’t you do something? My skirt looks so old.”

“When there is silk in the cupboard, no one notices the rags,” said Bubbie.

“What do silk and rags have to do with anything, Bubbie?” said Rachel.

“Someday you’ll know,” Bubbie said. Plop. In went another potato.

“Maybe,” said Mama, “if I’m very careful, I can save some wool to make you and Hannah something special.”

“What will you make, Mama?” Rachel asked.

Mrs. Berger smiled. “You’ll see,” she said, but she didn’t say anything else.

Rachel didn’t need anything special. She just wanted a skirt that was different from Hannah’s.

“Bubbie, Mama is going to make something special!” said Hannah.

“Just because my feet hurt doesn’t mean I can’t hear,” said Bubbie. She began grating the potatoes on the four-sided metal grater. There would be potato kugel for supper, Rachel’s favorite.

“I want to look just like Rachel, Mama.”

Bubbie wiped her hands on a dish towel and pinched Hannah’s cheek. “You’ll be twins, like Mollie and Simcha,” she said.

“I don’t want to be twins, Bubbie,” said Rachel.

“And why not?” asked Bubbie.

How could Rachel explain that she didn’t want to wear the same clothes as Hannah? After all, she was in third grade and Hannah wasn’t even in school yet. One minute they wanted her to be the big sister and the next minute they wanted her to be like baby Hannah.

“If we wear last year’s skirts, at least may I get new buttons for them, Mama?” she asked. “I’ll get one kind for Hannah’s skirt and a different kind for mine.”

“Well, I was going to use the buttons from one of your outgrown dresses,” said her mother.

“Those were baby buttons, Mama. Can’t I get new ones?”

“Sometimes an extra carrot in the pot makes the stew worth eating, Beryl,” Bubbie said. “Especially if it’s the last good stew for a while.”

Rachel had no idea why Bubbie was talking about carrots and stew when it was buttons and skirts Rachel and her mother were discussing. But she knew her grandmother was somehow on her side. She crossed her fingers for luck.

Mrs. Berger looked at Rachel, sighed, and reached into her purse. She took out a nickel and handed it to her daughter.

“This is all I can give you. Look for the sale buttons at Mr. Solomon’s store.”

“Oh, thank you, Mama,” said Rachel.

Suddenly Mama’s eyes lit up. She looked past them as if she were seeing something no one else could see. She wrapped the wool around her shoulders.

“This is how I’ll walk when I have the fancy uptown ladies as my customers,” she said.

She held out her arm for Rachel. Together they swept around the tiny kitchen like royalty

. Hannah dashed next to Rachel.

“Me too,” she said. “Can I be fancy, Mama?”

“Yes, little Hannah.”

They made their way toward Bubbie.

“Come, Bubbie,” said Rachel. “Be fancy with us.”

“With these swollen feet?” Bubbie waved them away.

“Goodness,” came a voice from the doorway. “It’s a surprise parade!”

“Papa!” said Hannah.

She left the group and threw herself into his arms.

“We were being fancy, Papa.”

“So I see.”

“Samuel,” Mrs. Berger said. “I didn’t hear you come in. We were pretending to be grand ladies.”

Smiling, she refolded the material and put it back in the brown paper.

“Sit, Samuel. You must be tired from standing all day in the shoe store. Supper will be ready in a little while. Rachel, set the table.”

“The store was busy today with the holidays so close,” Mr. Berger said as he watched the meal preparations. “I wish you could have a new pair of shoes too, Beryl.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Mrs. Berger. “I have something better than shoes.”

Mrs. Berger told him about her new job as dressmaker.

“I know my designs will work,” she said. “I just know it! After I sell a few dresses, I’ll buy a secondhand sewing machine so I’ll be able to work even faster.”

“Hmm,” said Mr. Berger. “Well, I guess we will have to be even more careful with money for a while, then. Though I’m sure you’ll soon have customers knocking at our door.”

Rachel felt the heat of the nickel in her hand. How much of a dream could it buy?

Mama went about cooking while Bubbie mixed the potatoes with grated onion and put the kugel into the oven. Rachel put the plates, each one different from the others, around the small wooden table. Hannah carefully laid a fork and spoon at each place.

“You are grand ladies,” Mr. Berger said.

He got up and patted Mrs. Berger’s hand.

Rachel's Roses

Rachel's Roses